2026-01-29

Vol.23

Creative Director

Yoshiaki Kasatani

-

Unconscious Creativity and Labels Imposed by Society

-

Beyond the Welfare Lens

-

The Boundary between Art and Design

-

The Gap between Inner Nature and Outward Reality

-

Tolerance Cultivated Through Setbacks

Riding the momentum of their instant connection at their very first meeting, Yoshiaki Kasatani, creative director and filmmaker behind the film Jizo Libido, and Masakazu Shigeta, founder of the skincare brand OSAJI who is deeply involved with welfare facilities for people with disabilities, come together for a dialogue to explore the root of expression. The conversation takes place at Atelier Yamanami, a welfare facility for people with disabilities in Shiga Prefecture, to which Kasatani has devoted himself for over thirteen years. Finding unconscious obsession in works born from an irresistible impulse to create, the two uncover the fundamental difference between art and design. Why are works created at Atelier Yamanami so highly valued overseas? What does creative practice nurture in artists: is it self-esteem or self-respect? Isn’t it tolerance, above all, that society needs as its fundamental attitude to evaluate art equally, regardless of whether it was created by people with or without disabilities? These questions lead the dialogue from our individual relationship with art to broader questions about the shape society should take.

“I was struck by how fundamentally different Mr. Kasatani’s perspectives on ‘Welfare x Art’ were from my own.” (Shigeta)

Masakazu Shigeta: This is my first visit to Atelier Yamanami(*1). I feel I’ll need some time to fully take in what makes this place so compelling, but I’d say what struck me most was a very pure thought: how is it that works created so unconsciously can feel fully realized?

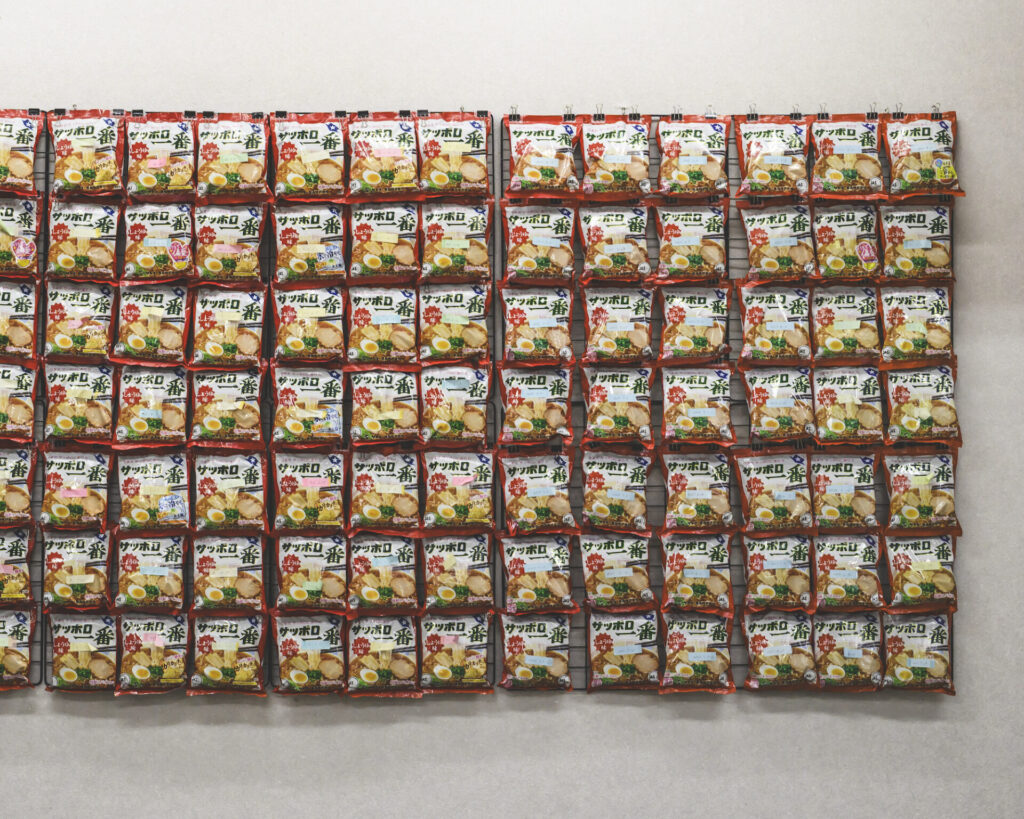

Yoshiaki Kasatani: The atmosphere and the exterior of the facility have changed since my first visit thirteen years ago, but the people who’ve been here for a long time haven’t changed at all. Some of them improve their skills over time, but for the most part, I feel many have spent these thirteen years doing the same things. That’s what makes it so cool — and also something that I feel can’t be imitated.

For people at Atelier Yamanami, creation is not optional — they are always driven by an irrepressible need to create. I’m always overwhelmed by the intensity of feeling that comes through powerfully in their work.

Shigeta: I’ve been visiting PICFA, a welfare support facility for people with disabilities in Saga Prefecture, for many years. There, the style itself doesn’t really change, but as you keep visiting, you feel the work becomes more refined.

As for Atelier Yamanami, I don’t sense that kind of visible change. And yet, there are so many works that make you purely feel, “I’d want to display this in my home.” It might sound odd to say it was unexpected, but I can’t help wondering what makes this possible, and that’s what sparked my curiosity.

Kasatani: That deep commitment to creation is probably the core of their works.

——I understand that the connection between the two of you began when you attended a solo exhibition in Osaka held by your mutual acquaintance, musician and poet Mr. Madoki Yamasaki. Even though it was your first meeting, you seemed to have hit it off immediately over drinks at the reception.

Shigeta: We happened to be sitting across from each other at the reception, and out of nowhere, he said, “Mr. Shigeta, I like you!” (laughs)

Kasatani: I’d had quite a bit to drink, so I don’t remember it clearly.

Shigeta: It might sound presumptuous to say this to someone older and more experienced, but even though it was our first meeting, I had a strong feeling that we’d become close friends. I wanted to talk to him more to better understand him.

The day after we met, I watched Jizo Libido, a film directed by Mr. Kasatani. Until then, I’d been observing things like “Welfare x Art” from a certain distance. But when I watched that film, I was struck by how fundamentally different Mr. Kasatani’s perspectives on that world were from my own.

Kasatani: Which part made you feel that way?

Shigeta: The message at the very end of the film — “We want to strip away the labels imposed by a barbaric society that sees individuality as disability.” — deeply resonated with me.

I thought we had to have a conversation within the context of this Idealism series, so I immediately reached out to propose this dialogue.

Kasatani: Thank you so much. I never imagined that the message would lead to an invitation like this. I immediately looked through the Idealism series website after the offer, only to find that so many accomplished people were speaking so eloquently. To be honest, it intimidated me a little. (laughs)

I thought for a moment I would decline, but I realized there would be a lot we could talk about. So I came today prepared to speak openly about everything.

Shigeta: Watching the film made me feel that my understanding of art had deepened, even if only slightly. In the film, it’s described how people with disabilities often draw most intensely when they’re not feeling well — how drawing allows them to coexist with, or confront, their own physical discomfort.

A sense that without drawing, they might not survive, or that without it, they can’t hold themselves together. That kind of “compulsion,” in a way, creates a kind of resonance. That somewhat vague realization helped me better understand art.

“At first, I had the mindset of ‘supporting’ them. But as I spent time interacting with people with disabilities, I quickly realized that I was the one learning far more from them.” (Kasatani)

——What initially led you to start visiting facilities for people with disabilities?

Kasatani: It began with the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. I went to the affected area, thinking there must be something I could do. But when I saw the devastation with my own eyes — damage far beyond anything I had imagined — I experienced, quite literally, what it means to be frozen in place. I was unable to do anything. I felt as if my profession as a designer was completely useless, and I fell into a mild depression.

Still, after returning to the office, I discussed with my staff whether there was something we could do. That’s when one of them said, “Even if we can’t contribute directly to disaster recovery, you’ve been saying for years that you wanted to do something to support people with disabilities, haven’t you?” Hearing that, I decided to start by helping the people closest to me, so I visited a nearby welfare support facility for people with disabilities.

——What did you do there?

Kasatani: I was allowed to visit the facility regularly under the pretext of creating a book — a kind of reportage documenting the realities of life there. Looking back now, it’s a little embarrassing, but at first, I was very much working on it with the mindset of “supporting” them.

But, as I spent time interacting with people with disabilities, I quickly realized that I was the one learning far more from them. What struck me most was the creative environment. Although I knew about art by people with disabilities as knowledge or information, it was the first time I had seen it firsthand. Recognizing their creativity far beyond my imagination, I abruptly shifted to focus on a project to introduce their art to the world.

The first thing we did was introduce their work to collectors of outsider art worldwide through the internet. In my broken English, I sent emails saying, “There’s a Japanese artist who draws something like this — what do you think?” To my surprise, a famous collector replied, “Tell me more,” so I went to France to explain in person. The work ended up selling for several hundred thousand yen. But rather than feeling happy, I felt a deep sense of discomfort.

Why are these works, ignored in Japan, highly valued overseas? I couldn’t understand why Japanese people pay no attention to these works. Even when we held an exhibition in Japan, visitors tended to view the art only through the lens of “welfare.” I kept thinking about how we could encourage people, including young people, to engage more purely with their work, simply as art. That’s how I started a project focused on making clothes, which eventually evolved into the brand DISTORTION3.

——How did people respond once you began working on making clothes?

Kasatani: Japanese buyers, as I’d expected, evaluated the work through the yardstick of “whether or not the artist has a disability,” with an attitude that felt like, “I’ll buy it to support them.” French buyers, on the other hand, didn’t ask for any background explanation at all. “I’m ordering this because I like it, and I don’t need any explanation beyond that.” Hearing that, I honestly thought, “That’s incredible.”

——That contrast seems to symbolize a broad issue within Japanese society.

Kasatani: I’ve faced various forms of criticism over the years, but I’ve always believed that there’s still so much more that can be done as a designer. I’ve held onto that belief, and that’s how thirteen years have passed.

“As someone who makes consumer products, I strongly believe that art and design must not be confused.” (Shigeta)

Shigeta: One of the topics I felt I wanted to talk more about with Mr. Kasatani at our first meeting was the boundary between art and design, and the balance between objectivity and subjectivity to create products. I believe that everything ultimately has to be systematized, and in that process, clearly understanding the boundary between art and design is extremely important.

Kasatani: That’s quite a challenging theme. But in my view, I’ve always seen art and design as completely different things, even before I encountered Atelier Yamanami.

Shigeta: So, where do you draw that line?

Kasatani: First of all, design never begins on its own — it always starts with a client. A company faces an issue and wants it solved; the designer then visualizes the solution. Therefore, there is almost no room for self-expression. Art, on the other hand, begins with the artist’s desire to create. Art is self-contained, while design isn’t.

Shigeta: No matter how objectively you explain a product, saying, “We’ve made this because there’s a need,” I don’t think a product is worth anything if the person who made it can’t love it. At the same time, even if you create something you deeply love on a subjective level, it can’t be called a product if no one needs it objectively. That’s why the balance between the two is important.

Kasatani: The reason I’m so fascinated with the work of Atelier Yamanami is precisely the fact that they are not creating for someone else. Almost everyone here only faces the work when they draw. They draw with extraordinary concentration and lose interest once they finish.

When I design or make films, I feel a sense of achievement and fulfilment once I’m done, and I immediately want others to see and evaluate it. In that sense, my creative purpose is directed outward. Realizing that made me painfully aware that I can never catch up with them as a creator.

Shigeta: Visiting Atelier Yamanami today made it very clear to me that art and design are completely different. It might be a sensory rather than a logical realization, but recognizing that difference feels incredibly important — and, in a way, fortunate.

I believe there’s a real danger in conflating the two. Especially these days, I see many risky projects where work is commissioned based on expectations of a designer’s “authorship.” Even though a brand has a solid core, foregrounding the style of a well-known art director and creative director often leaves you unable to tell what the core even was. There’s no need for me to sound the alarm publicly, but as someone who makes consumer products, I strongly believe that art and design must not be confused.

Kasatani: That’s a downside of blurred boundaries.

Shigeta: It’s difficult to define exactly where the line should be drawn, but one of the criteria is the presence — or absence — of obsession. Design operates on the major premise that it must not harm others. Design has to embrace or collaborate with people. Even when a design seems to contain a certain obsession, that must be a fake — something staged.

Kasatani: Exactly.

Shigeta: What I felt through the work of the people at Atelier Yamanami was a real sense of obsession. As I walked through the space, there were moments when fear and beauty collided within me — works that unsettled and mesmerized me at the same time. That kind of obsession may be what separates art from design.

In fact, the artists I know are all obsessive in their own way — bad drunks, obsessed with pointless fantasies, all of them. Those who can’t express that straightforwardly tend to lose their creative drive somewhere along the way.

Kasatani: That might be true. In the text I wrote for AYAW2(*2), Atelier Yamanami’s second collection of works published in September 2025, I mentioned that seeing their work evokes feelings like fear, nervousness, or a shiver down our spine — emotions we rarely experience in daily life.

At the same time, there are moments I feel a kind of nostalgia. Why is it that the works that I know I could never match evoke these feelings? The sense of “unknowability” may itself be a form of obsession.

——Perhaps it’s something you can’t experience through design.

Kasatani: We are probably finding, in their work, things we once had in our childhood but have abandoned as we grew up, entered society, and learned how to align with others. I almost never feel that through design.

Shigeta: That’s really interesting. Whenever we brainstorm internally, I tell my staff that “Brainstorming is meaningless unless it consciously engages with ero guro — the erotic and the grotesque.” If you strip away those impulses and make something overly gentle and polite, it becomes endlessly replaceable. It might sound harsh, but unless a product responds honestly to something like the ugly parts of human nature, it won’t truly attract people.

——So products that perform “wholesomeness” are inherently replaceable.

Shigeta: I’m not saying that being replaceable is inherently bad. But in a world already overflowing with things, I often ask myself whether we really need to create more products like that. That’s why, when I brainstorm, I only do it in environments where we can let loose — over drinks, or at a local Chinese restaurant under the tracks in Ameyoko, Ueno. Without that, I don’t think you can create anything that truly unsettles people’s senses or speaks to their deeper nature.

I also believe there must be meaning in the fact that the boundary itself is never completely clear. There is a gradient between extreme obsession and absolute cleanliness. And perhaps it’s precisely because that middle ground exists that making things remains a lifelong pursuit — one where you never quite arrive at a single, definitive answer.

“The era of saying ‘You did such a great job despite having a disability’ ended long ago.” (Kasatani)

Shigeta: For the past two years, I have given a social studies lecture to fifth-graders once a year under the theme “Japanese Industrial Production and Our Lives.” In those classes, I asked the students about the difference between the market-driven approach and the product-driven approach.

Of course, they’d never heard those terms before, so I explained their meanings first, and at the end, I asked them to raise their hands to choose which approach they’d like to work with: the market-driven approach, which responds to clearly defined consumer needs, or the product-driven approach, where you create something no one has even imagined yet. Out of 30 students, 29 chose the product-driven approach.

Kasatani: That’s surprising.

Shigeta: Students today tend to give very “correct” answers — they rarely miss the mark. I assumed everyone would choose the market-driven approach, only to find that only one did, and almost all of them had a mindset of wanting to do something different from others.

At the end of the class, I told them, “If you want to work with the product-driven approach, you need to see things from a different perspective from others, and when your opinion is not aligned with others, you must make every effort to explain your idea and earn their understanding.”

What giving the lecture made me realize was how wide the gap is between our inner nature and what we actually do. New educational models encourage free thinking and active idea-sharing, but the process of idea generation itself becomes too formulaic. What looks like open discussion turns into a search for a safe compromise — reading the room, prioritizing harmony, and adjusting to the group.

People may want to be different from others, but they also fear standing out. That gap can be one of the biggest obstacles to true innovation. That’s why I strongly feel that what Mr. Kasatani is doing can create ripples of change.

It also reminds me of the difference between Japanese and French buyers. Japanese buyers often can’t fully commit unless they can logically justify why something is good, while French buyers are more willing to choose something because they respond to their initial impulse of “This is cool.”

Kasatani: I started these activities to change what felt like a distortion in Japanese society, and in that sense, I think the environment surrounding art by people with disabilities has changed dramatically. More and more companies are now incorporating work from Atelier Yamanami. While I’m amazed at how quickly things have shifted, I also find myself feeling uneasy more often.

Shigeta: In some cases, it’s being used as a tool to improve the company’s image.

Kasatani: Exactly. One of the things that I didn’t want to do from the beginning was simply print art by people with disabilities onto pre-existing clothing templates. That’s why I always select the fabric first and create patterns from scratch, each time, based on the inspiration I gain from a particular artwork.

However, as public interest in art by people with disabilities has grown, I’ve seen more and more examples that feel like little more than direct transfers — almost like stickers being slapped on. That makes me a bit sad. I feel something I felt thirteen years ago once faded, but it’s coming back now.

I’m genuinely happy that art by people with disabilities — once completely overlooked — is finally being recognized. But I can’t help but want to ask, “Is it truly being respected?” Sometimes it feels as though anything can be pasted on under the label of disability art, and companies simply say, “This is good, isn’t it?”

Shigeta: Is your ideal a world where there’s no distinction between art by people with and without disabilities, like Art Brut or outsider art?

Kasatani: Yes, ideally, those distinctions would disappear. Cookies are better when they taste better. Art is the same — what matters is whether it genuinely moves you. The era of saying “You did such a great job despite having a disability” ended long ago.

In the end, it is not about whether the artists have disabilities or not, but whether the work itself is good — that’s the ideal. But I have to admit we’re not there yet. While there is no need to explicitly announce that “These works are created by people with disabilities or chronic illness,” it’s still difficult to gain understanding without at least subtly suggesting that context. Finding the right balance is quite hard.

“The disputes over harassment are a kind of war of saying ‘No’ to values that don’t align with one’s own beliefs.” (Shigeta)

Shigeta: I myself can’t confidently say that it is nonsense to use words like Art Brut or outsider art. However, people with and without disabilities will never be the same — they are physically different. And precisely because of that, it should be understood as a way to understand what tolerance means.

Kasatani: Tolerance?

Shigeta: People often say that “We should try to understand others,” but I believe it’s impossible because we’re simply different. What truly matters is to know that there are people who are different from you.

Furthermore, I also feel a bit uncomfortable with the idea of “not denying someone or something even if you can’t empathise with it.” If there’s a moment when you feel like rejecting something or someone, it’s okay to reject. What’s important is not pretending as if those reactions never happened.

Kasatani: Speaking of your involvement with people with disabilities, unless you know someone like that around you, it’s hard to arrive at those kinds of perspectives in the first place.

Shigeta: The lack of tolerance is why arguments so quickly escalate into “What you do is a form of harassment.” If you say something strictly for someone’s growth, it’s completely different from mere harassment, but many people can’t tell the difference.

Some people are always saying “No” to ideas that differ from their own. In the end, the disputes over harassment often turn into a kind of war — a battle of saying “No” to values that don’t align with one’s own beliefs.

——Is there any effective way to cultivate tolerance?

Shigeta: I think it comes down to how many setbacks you’ve experienced. These days, many people haven’t experienced real setbacks — and I suspect that’s especially true for those who lack tolerance. I imagine you’ve faced a lot of hardship, too, Mr. Kasatani, much like I have.

Kasatani: (nodding deeply) Exactly.

Shigeta: I believe that, as a result of repeatedly experiencing frustration of not being understood, I’ve developed the tolerance I have today. I’ve always tried to think differently from others — whenever people chose option A, I deliberately chose option B. That’s why people around me often thought of me as an annoying person.

Speaking of elementary students I mentioned earlier, if I had told them, “You can say whatever you want,” I might have heard ideas I could never have imagined. But people instinctively try to avoid setbacks and the pain of being excluded. As a result, they only select what everyone already agrees is “good.” I want to tell them, “You should experience as many setbacks as possible, because it will make you kinder in the long run.”

Kasatani: This constant social pressure to search for the “correct answer” is closely related to education. There are currently 94 members at Atelier Yamanami, and if we were to promote them by saying every single one of them is outstanding, that would be a dishonest platitude.

Each person has their own likes and dislikes, and that’s simply what it means to be human. Precisely because I’m an outsider, I can only introduce what I find compelling. That stance will never change.

——Looking ahead, do you have any goals for your involvement with Atelier Yamanami?

Kasatani: My goal is to create a situation in which artists from Atelier Yamanami compete solely through their work, without profiles or background information. I want to build a system where people can encounter their artworks and feel something purely, without any prior context. Achieving that would be a step toward the ideal of removing the distinction between art created by people with and without disabilities.

——The theme of this Idealism series in 2025 was “Self-Respect.” Art is often said to enhance self-esteem, but it can also help cultivate self-respect.

Shigeta: I think treating self-esteem and self-respect as the same thing misses the point. The subject of self-respect is “We” — it includes a sense of gratitude toward the people who have shaped who you are and who support and value you. Self-esteem, on the other hand, is centered on “I.” I feel self-esteem carries the nuance of affirming yourself, while self-respect feels closer to not denying yourself.

Kasatani: The word self-esteem is often used casually, but self-respect is more precious. Speaking personally, my current sense of self-respect is built on everything I’ve cultivated over 56 years. And perhaps it’s not something that belongs to me alone, either.

Shigeta: People grow precisely because they can’t fully affirm themselves. If you affirmed everything about yourself, there would be no need to grow at all. Honestly, I sometimes wonder whether the moment when I can truly affirm myself will ever come before I die. If that moment arrived at some strange time out of nowhere, wouldn’t it feel unsettling?

Kasatani: I feel the word “self-esteem” itself emerged quite recently.

Shigeta: Yes, I agree. Drawing contributes more to cultivating self-respect than to boosting self-esteem.

Kasatani: That may be true. I believe it’s definitely a theme that we should explore more deeply later — over drinks.

Shigeta: Absolutely. Let’s do that.

Notes:

*1_Atelier Yamanami

Located in Koga City, Shiga Prefecture, Atelier Yamanami is a welfare facility that provides a place for people with intellectual disabilities to express their individuality through creative activities. Under the concept of “Each person lives as themselves, in their own natural way,” the atelier has supported diverse creative activities since its establishment in 1986, including pottery, painting, and textile arts.

Current facility director Masato Yamashita, who respects each member’s expression, has devoted himself to creating a creative environment unbounded by convention. As a result, the atelier has produced numerous outsider artists.

After his first visit to Atelier Yamanami in 2012, Kasatani launched a project called “PR-y,” where he promotes the appeal of the atelier’s artworks worldwide. The atelier continues to be a vital hub of contemporary art, demonstrating the fundamental power of artwork created by people with disabilities.

AYAW2

Published in September 2025, AYAW2 is the second collection of artworks by Atelier Yamanami. Following the previous collection, AYAW, the book contains over 500 artworks full of life force created by artists at the atelier across more than 600 pages. This extensive collection of images fully conveys the diversity and depth of individual expressions, and also serves as a precious archive of the trajectory of creative activities at Atelier Yamanami. Kasatani served as editorial supervisor. Kasatani and Shigeta met for the second time at a book launch event in Daikanyama, Tokyo.

Profile

-

Yoshiaki Kasatani

Born in 1969 in Osaka, Kasatani is the vice president of RISSI INC. As a creative director, he worked across various fields, including advertising, graphic design, video production, and space design, before beginning to direct a project called “PR-y” in 2011, in which he devoted himself to promoting outsider art free from conventional art frameworks. He creates portrait collections of artists and serves as a facilitator, connecting them with galleries and research institutes overseas.

Following his encounter with Atelier Yamanami, Kasatani directed the 2018 documentary Jizo Libido, exploring the origins of their creativity and how society views it. The film was shown in Japan and abroad. His curiosity continues to challenge taboos between art and society.

-

Masakazu Shigeta

After working as an engineer in the music industry, Shigeta began his career as a cosmetics developer in 2001. From 2004, he worked on various cosmetics brands in the healthcare business of Nitto Denka Kogyo Co., Ltd., a metal surface treatment company founded by his great-grandfather. In 2017, he founded “OSAJI,” a skincare lifestyle brand, and became its brand director. In 2021, as a new store of “OSAJI,” he produced “kako,” a specialized shop for home fragrances and perfume in Kuramae, Tokyo. In the following year, he opened a combined shop of “OSAJI,” “kako,” and a restaurant, “enso,” in Kamakura, Kanagawa. In 2023, utilizing the technical skill of Nitto Denka Kogyo, he launched a pottery brand, “HEGE,” and in October of the same year, he became CEO of OSAJI Inc. He also has published books on beauty and held cooking classes and events focusing on food, which is the origin of beauty. He released a collaborative album with F.I.B JOURNAL called “Gensho hyphenated” in November 2024 and has been expanding the range of activities.

Publications

Taberu Biyou (Eating for Beauty) (SHUFU TO SEIKATSU SHA, 2024)

42-Sai ni Nattara Yameru Biyou, Hajimeru Biyou (Beauty cares to quit and start when you turn 42) (Takarajimasha, 2022)

Information

Jizo Libido

Jizo Libido is a documentary film directed by Yoshiaki Kasatani that focuses on artists with intellectual disabilities who attend Atelier Yamanami. While their works have drawn growing attention in Western art scenes, the artists themselves remain indifferent to evaluation or completion, continuing to create driven purely by impulse. Through stylish visuals and a carefully crafted musical score, the film portrays this everyday reality.

By examining the libido — the primal life force — at the heart of the film, Kasatani explores the source of their pure yet earnest creativity. The words the artists speak in front of the camera and the moments in which they immerse themselves completely in the act of creation confront the audience with a fundamental question: What is art?

https://www.jizolibido.com

DISTORTION3

Launched as part of the project “PR-y,” which promotes creative activities of people with disabilities, DISTORTION3 is a fashion brand founded in 2013 by creative director Yoshiaki Kasatani. Inspired by the raw and earnest artworks of artists with intellectual disabilities born at Atelier Yamanami in Shiga Prefecture, the brand develops its unique collection free from convention by elevating these works into textile designs. Masahiko Maruyama, who has been presenting his own brand at Paris Fashion Week since 2008, serves as designer. The brand aims to connect artists’ primal and pure energies with society through fashion as a platform.

-

Photographs:Eisuke Komatsubara

-

Text:Masahiro Kamijo

-

Locations:Atelier Yamanami

NEWS LETTER

理想論 最新記事の

更新情報をお届けします

ご登録はこちら

ご登録はこちら

メールアドレス

ご登録ありがとうございます。

ご登録確認メールをお送りいたします。